Dabney: ‘You owed your country a defense’

Published 6:10 pm Saturday, November 5, 2016

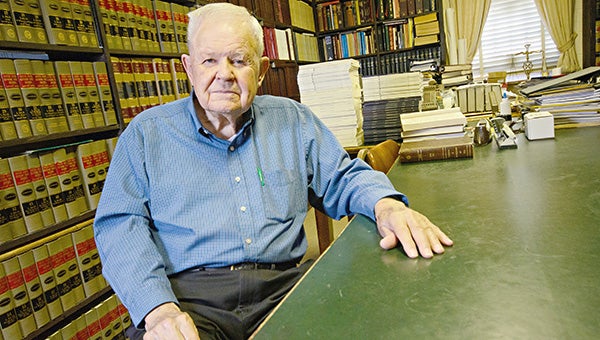

- VETERAN: Lucius B. Dabney Jr., sits in the Dabney & Dabney law office on Walnut Street and recalls his time at the Virginia Military Institute, services in World War II and the Korean War.

By Lana Ferguson

The Vicksburg Post

Stepping into the Dabney & Dabney law office on Walnut Street is like stepping back in time.

So is talking to Dabney himself.

When he closes his clear blue eyes, his brow furrows, and he remembers.

Surrounded by typewriters, ancient maps and book from another era, Lucius B. Dabney Jr., 90, can still vividly describe working under his father and uncle in the law office as a teenager, rooming with five brother “rats” at Virginia Military Institute, and being called to serve his country in World War II, then again in the Korean War.

Born Nov. 23, 1925, Dabney was an only child, a product of the Great Depression, which he said didn’t seem to end until World War II began.

At age 13, Dabney’s father gave him a hand-me-down typewriter. He loved it and still does. It’s tucked away in the library of the law office. He didn’t know he’d get the opportunity to work with many more.

During his second semester at VMI, where he was studying engineering, the draft age was lowered from 21 to 18. The draft was calling Dabney to duty and on March 7, 1944, he was inducted. Two months later, he was at Camp Shelby.

“The war was on,” said Dabney. “You owed your country a defense and you got busy.”

There were 30 soldiers in his platoon.

The newly drafted men stood at attention in front of corporals.

The first corporal asked truck drivers to step forward. About half the soldiers did. They were marched off. The second corporal commanded the soda jerks step forward. They were marched off as well. A final corporal came out and asked Dabney, “What do you do?”

“I typewrite, I cut stencils, file papers, and so on,” Dabney said. “He said, ‘Go help the company clerk,’ and I had a desk job the rest of my time in Shelby.”

After basic training at Camp Crowder, Missouri, he was assigned to a signal training regiment, where he would spend months training in teletypewriter repair, switchboard repair, and power equipment repair.

“All of us kind of wondered why we were staying around there and I think they did too,” Dabney said. “They wondered why we hadn’t gotten ordered to go someplace for sure.”

From there he was sent to Camp Beale, California, a staging area for the war in the Pacific. They stayed but once again never received any orders to head overseas. All 900 trained signal corps technicians were eventually sent to Camp Livingston, Louisiana to make room.

There, they were allowed to visit home for a week, before going to Fort George Mead on the outskirts of Washington, D.C.

“When we got there, they said, “Where have you been?’ We responded almost all in unison, ‘All over the United States,’” Dabney said. “We had been lost.”

Now back on track, Dabney and 4,000 others boarded the Marine Tiger, a 10,000-ton ship, and sailed across the North Atlantic until they landed in Le Havre, France. From there, they rode a train to Roermond, Holland,

“We hurried and waited and they sent us on to Brunswick, Germany,” Dabney said. “I was assigned to the 310th Signal Battalion, which was the signal unit for the Ninth Army Headquarters. The war was not yet over.”

The Allies were planning to invade Japan and Dabney’s unit was scheduled to join what expected to be a long and brutal campaign to take the Japanese homeland. Luckily, Japan surrendered.

Dabney’s final stop was with the 51st signal operation battalion at Camp Polk, Louisiana before he went home in May 1946.

Almost as soon as he arrived back home, he went to the University of Mississippi to study law.

He had always wanted to be a lawyer.

As a teenager, Dabney had worked every day after school with his father and uncle in their law office, running errands, stacking books on shelves, and teaching himself to use the typewriter.

At Ole Miss, where he roomed with Vicksburg friends, Bill Rawroth and Nathan Levy, he joined the ROTC and got his officer’s commission.

Dabney graduated in August 1949 and returned home to practice law.

He transferred from the Army Reserves to the National Guard because Vicksburg had the 106th combat engineering battalion.

In the Korean War, Dabney was called to active duty again as a first lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. They were sent to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, on Jan. 16, 1951, for about eight months. His orders to Korea arrived in mid-October.

When Dabney got home, he returned to the law office and it was like he had never left.

Like so many men from “the greatest generation,” he doesn’t regret a moment of his wartime service. It was his duty, he says, and “we did what we had to do.”

Despite being almost 91, he still goes to work Monday through Friday and on Saturdays “if necessary.” He is the sixth generation to work in the Dabney & Dabney law office, making it the oldest in the state.

When he isn’t in the office, Dabney spends time with his wife Allene, who he married in 1964, and their cat Rudolph, named after one of his VMI rat brothers.

He still takes to heart advice his father gave him in 1949.

Walk an hour before breakfast every day, which he does at 5 a.m. “I don’t run. I don’t jog. I walk,” Dabney said. “That’s why I am still here.”