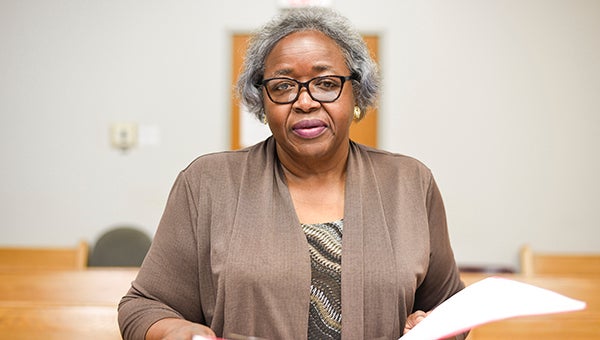

New life for Youth Court advocate

Published 9:40 am Monday, June 12, 2017

- (Courtland Wells/The Vicksburg Post)

June 30, Joyce Edmonds will walk out of the offices of the Warren County Youth Court building and begin a new life.

After working more than 30 years in social work, the last 10-1/2 as director of the Youth Court’s guardian ad litem program, the Vicksburg native is retiring to spend more time with her family.

“I knew I wanted to be a social worker since I was in the ninth grade,” Edmonds said, discussing the path that brought her to the position she now holds.

It began with her degree in social science with emphasis on sociology from Mississippi Valley State University and later enhanced with a master’s degree in community counseling, and positions with the state Department of Human Services as a social worker, eligibility worker, adoption specialist, area social work supervisor and supervisor of the food stamp division in Vicksburg. She also worked as rape crisis director and domestic violence supervisor with Haven House.

In 2007, Judge John Price asked her to develop and head the court’s volunteer guardian ad litem program.

“This position is his brainchild, because he wanted lay guardian ad litems to work with children,” she said.

A guardian ad litem can be an attorney and/or a volunteer that is appointed by a judge to represent a child in court proceeding and serve as the eyes, ears and voice for a child in court.

“That guardian ad litem is supposed to look out for the best interest of the child. We still can appoint lawyers, but lay guardian ad litems have more time to work one on one with the child. So we use a combination of both. “

Guardian ad litems, Edmonds said, investigate allegations whether a child been abused or neglected, or is in need of supervision, can be involved in resolving custody disputes and works with delinquent children.

Sometimes, she said, youth court workers will see children brought in for delinquent acts and talk with the child, and the cause could be some neglect or abuse or some inappropriate sexual activity going on with the child.

“At that point, a guardian ad litem is appointed and they investigate (the) cases; they recommend what needs to be done to correct the family situation prior to the child being returned to the home or custody of the parents.”

When the guardian ad litem is appointed, she said, they must meet with all the parties involved in the case. They are allowed to go to the schools and talk with the child, and to the home to investigate and see which family members are interested in the child “or can give us insight about the child’s situation, and that are available to help find places for children.”

“It is our goal always to place children either in their home or with other family members that can keep the child while the parent is rehabilitation or doing whatever they need to make sure the child has a healthy home. We have 15 volunteers; when I first started out with three people.”

The guardian ad litems, Edmonds said, “Are unique people, because at first, you have to have the interest in people, you have to be able to work with children from all different status of life all different cultural background, and you have to be able to separate your values from that family’s values.

“All of my volunteers except for three are retired. They have worked with children, worked with families; they don’t try to force their values on other people, but they are trying to show them a different way of dealing with different issues.”

She is responsible for recruiting, training and supervising the guardian ad litems, who must annual training certified by the Judicial College at Ole Miss. She goes to training programs and selects the programs for the local training sessions.

The speakers who present the programs, she said, “Are considered experts, and deal with ethics and issues in dealing with children.”

Serving as a guardian ad litem is stressful, Edmonds said, but it can be very rewarding.

“It’s very rewarding, because you actually see children that really haven’t been exposed or exposed to too much, and we recommend that they go to counseling and we can actually see the difference it makes. We actually see people who have gone through the program and now they are coming back, and you see them, and kids are back with the family.”

The program is stressful, she said, because the guardian ad litem knows what the family needs, but they’re unable to get the necessary services because of financial reasons or they don’t think they need it, or the service is not there.

The most traumatic thing, she said, is for the child to be taken from the family, but sometimes it needs to be done because the parents come in under the influence of drugs and neglect children.

“Children always want to be with their own families, and that’s stressful to see that, and the majoritiy of the children do get back with family or parents, but we occasionally have to recommend termination of parental rights. And that is the most stressful part, but the children have the right to permanency.”

After a guardian ad litem has completed their investigation of a case, Edmonds said, they consult with her.

The report must be in writing and include who the guardian ad litem interviewed and when. The report with their recommendation is then presented to the judge, who must accept the recommendation unless he is able to show overriding evidence to the contrary.

“They recommend what’s in the child’s best interest; they figure out what’s going on,” she said, adding guardian ad litems have been known to stay on cases for more than a year before their investigation is complete.

Those recommendations can include temporary custody at a home like The Children’s Shelter and programs the parents must attend if they want to get their children back. One of the charter board members, she said The Children’s Shelter has been a tremendous plus for the youth court.

Sometimes parental rights are terminated when the parents don’t cooperate. “ I don’t think they (parents) do it deliberately,” Edmonds said. “I think basically, every parent loves their child.”

“We find most of our parents who go through drug rehab, they get their children back. Every case is different, and that’s the way we have to look at it, because we can’t go in and do the same thing, the same way on every case. We have to look at each case individually.”

Seeing the success stories, Edmonds said is the reward of working in the program.

“I always say, ‘I have to sleep at night,’ she said, “And I believe I was called to do this; I believe we’re called to do certain things. I know it’s not in my strength I do this. I’ll be prayed up when I come to work, because if not I couldn’t do it, because seeing children’s faces to be removed (from the parents) oh, it’s going to change their whole life.”