Vicksburg native Clyde Kendrick took winding path to the MLB draft

Published 11:09 pm Saturday, June 20, 2015

Clyde Kendrick sits in the dugout at Bazinsky Field. The former Vicksburg High star was selected by the Texas Rangers in the 27th round of the Major League Baseball draft earlier this month.

On a Greyhound bus, somewhere along I-20 in Louisiana, Clyde Kendrick woke up to find out he had realized one of his lifelong dreams.

The former Vicksburg High star snapped out of a nap and, with groggy eyes, checked his phone. It was blown up with messages on Instagram, Twitter and various other forms of social media congratulating him on being the 798th selection in the 2015 Major League Baseball draft, taken in the 27th round by the Texas Rangers.

“I’m asleep on the bus, and wake up to an Instagram notification. A friend of mine said, ‘I saw your name on TV,’” Kendrick said. “So I look, and I’m like, all right, it’s there. Sweet.’ Then the next thing I know, people are hitting me up on Snapchat. People are congratulating me.”

Before long, Kendrick was going viral on the bus, too.

Earlier in the trip he’d struck up a conversation with the guy in the next seat and two brothers from Miami who were traveling cross country. In moments, they were tweeting and sending out pictures of perhaps the most popular person ever to ride the bus from Portales, New Mexico, to Vicksburg, Mississippi.

“He’s taking pictures and saying the dude he’s riding on the Greyhound with just got drafted. They gave me a standing ovation,” Kendrick laughed. “Those other guys, I’m friends with on Instagram now and I’m still getting notifications.”

In the middle of the night, Kendrick had become an overnight sensation. The road there, however, was as bumpy as that Greyhound, and he knows that bus ride home was just the first of many he’ll take before he reaches the big leagues.

•

Kendrick was a two-sport star at Vicksburg High. He was a wide receiver for the football team’s record-setting offense in 2011 — he caught 54 passes for 634 yards and six touchdowns in his only season as a varsity starter — and was even better on the baseball field.

He hit .388 in three seasons as a starter, with 60 RBIs and 63 runs scored. He was also successful on 35 out of 40 stolen base attempts and one of the Gators’ top pitchers, and was picked to play in the Mississippi All-Star Game as a senior.

Kendrick got some buzz as a draft prospect in 2012, but nothing came of it and he signed with Hinds Community College. Once there, his relationship with head coach Sam Temple soon soured. Kendrick said Temple’s hard-nosed attitude, among other things, didn’t mesh with his own. Things came to a head when his younger cousin Acasia Rochelle Lee was killed in a car wreck in 2013.

“They wanted me to come practice, and I told them my cousin is in the hospital. From that point on, I was like, ‘I’m not coming to practice,’” Kendrick said. “That was one of my closest friends. It killed me on the inside, but gave me the motivation, too, to keep going and to do it for her.”

Kendrick left Hinds at the end of the 2013 season and found a home at Holmes Community College. The atmosphere, he said, still encouraged hard work but was a bit more forgiving, and it was a perfect fit. Kendrick thrived with his new team.

Clyde Kendrick throws a warmup pitch at Bazinsky Field. The former Vicksburg High star was selected by the Texas Rangers in the 27th round of the Major League Baseball draft earlier this month.

Playing as both a pitcher and an outfielder, he went 6-5 in 12 games and averaged 10.8 strikeouts per game — more than one per inning. He also hit .377, drove in 27 runs and stole 14 bases.

For the second time, Kendrick generated interest from major league scouts. And, for the second time, they passed.

Luckily, David Gomez didn’t.

Gomez was an assistant coach at Alcorn State from 2010 to 2013, and was well aware of Kendrick’s ability. His wife, Charity Gomez, was a teacher and volleyball coach at Vicksburg High while Kendrick was a student there, and the family lived in Vicksburg.

When Gomez left Alcorn to become the head coach at Eastern New Mexico University in 2014, he had no doubt who he wanted for his first recruit.

“When I got hired and moved out here, the first call I made was to Clyde Kendrick,” Gomez said.

Kendrick had gotten offers from Stillman College and Selma University in Alabama, William Carey in Hattiesburg, and Jackson State. Gomez, however, made an offer and a promise that was too good to turn down.

“He said, ‘If you come out here, I’ll get you drafted,” Kendrick said. “Right then, I was gone. That’s all I needed to hear.”

Eastern New Mexico, a Division II school in Portales, New Mexico, was far from the glamour of the Southeastern Conference programs Kendrick grew up watching. Its home stadium, 500-seat Greyhound Field, is smaller than some high school ballparks he’d played in. It was, literally, almost a thousand miles from home — 806 miles, to be exact.

It was also the big break Kendrick needed, and the place he’d transform from a pretty good ballplayer into one with serious pro potential.

•

In Mississippi, Gomez said it seemed like Kendrick was one of many great athletes in a talent-rich state and got lost among them. That was hardly the case in New Mexico. From the moment he stepped onto a baseball field in the Land of Enchantment, Kendrick was turning heads.

Before he arrived on campus at Eastern New Mexico, Kendrick went to play in a summer wooden bat league in Albuquerque. He ran a 60-yard dash in 6.38 seconds — anything under 6.60 seconds is considered fast — and his fastball topped out in the low 90 mph range.

“The first time he threw a ball in the state of New Mexico, he started getting calls from scouts,” Gomez said with a laugh. “I knew he would shine. Every first he did out here, people were like, ‘Oh man! Who’s this guy!?’”

Kendrick came to appreciate New Mexico, too. Even though it was the option furthest from home, he said that and the town’s small size made it easy to focus on baseball. About 12,000 people live in Portales, making it about half the size of his hometown of Vicksburg.

“It was a different atmosphere at Eastern,” he said. “But the town is so small, you didn’t have a choice but to focus on what you’ve got to do.”

Besides playing baseball, that included getting his grades in order. Kendrick failed English in his senior year of high school. He made it up and got a diploma by taking online courses, but the failed class continued to haunt him. He was academically ineligible for the fall 2014 semester and couldn’t practice with the team while he got his grades in order.

While he worked on that, Kendrick also kept grinding during his offseason workouts and made an even bigger impression than the one he’d made in Albuquerque.

“In the fall, we drove 10 hours to go to Arizona for maybe 15 scouts,” Kendrick said. “I hit 93 (mph) and they liked my pitches. That’s when I met Doug from the Rangers.”

“Doug” was Doug Banks, an area scout for the Rangers who is responsible for scouring Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah for talent. He took an interest in Kendrick, and the two formed a solid relationship.

“I felt confident with (Banks). He told me I could play, and I believed it and it happened,” Kendrick said. “I can’t do nothing but praise him.”

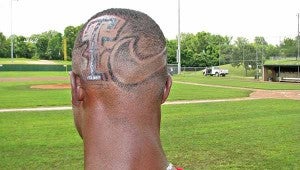

Former Vicksburg High star Clyde Kendrick shows off his new haircut, which features logos for the Texas Rangers and Nike. Kendrick was selected by the Texas Rangers in the 27th round of the Major League Baseball draft earlier this month.

Kendrick was finally able to get on the field for Eastern New Mexico this spring. Gomez, seeing Kendrick’s potential and future as a pitcher, limited his playing time as an outfielder, but Kendrick still hit .311 and went 6-for-7 on stolen base attempts in only 49 plate appearances.

“When he got on, we would put the take sign on and let him steal second, then third,” Gomez said.

On the mound, Kendrick continued to be a strikeout machine. He fanned 66 batters in 50 1/3 innings, and opponents hit just .192 against him. He struggled with his control, however, and walked 43 batters. Because of the walks, he had a 4.47 ERA that wasn’t indicative of his electric stuff on the mound. His fastball topped out at 95 mph this spring.

“The development he’s had from high school to now is tremendous,” Gomez said. “That has to do with his hard work. I could never imagine he could do what he’s doing now.”

Kendrick blamed his high walk rate — and a reduced velocity on his fastball — on not practicing in the fall.

“I honestly think I could’ve reached 97 if I’d practiced that whole time,” Kendrick said.

Banks and the Rangers didn’t seem to mind, and the Arizona Diamondbacks were also scouting Kendrick. Some chatter had him getting drafted as high as the fifth round.

When the second day of the draft, which encompassed rounds 3 through 10, had come and gone, however, Kendrick still hadn’t seen his name or gotten a phone call from either team. He got on the bus in Portales to head back to Vicksburg for the summer, and dozed off as the bus crossed the border between Texas and Louisiana.

•

Before his nap, Kendrick had struck up a conversation with his seatmate.

“On the bus, you don’t have a choice but to talk to somebody. It’s boring, and you can’t listen to music 24-7,” he said.

So, when he woke up and confirmed the news that he’d been drafted, the relatively obscure 27th-rounder broke the news to everyone on the bus and became the life of the party. The news soon went viral, and even people Kendrick said had dismissed him years earlier were congratulating him on social media.

“My motivators hit me up. That’s how the game is,” he said. “People that didn’t want to mess with you before, start messing with you.”

When he arrived back in Vicksburg, Kendrick had some business to take care of. The first thing was negotiating a contract.

Kendrick wanted a $50,000 signing bonus, but the Rangers — who have a little over $9 million to sign all 40 of their draft picks — offered $25,000. Kendrick countered with $35,000, and the two sides ultimately settled in the middle at $30,000.

Kendrick said he would’ve liked to have gotten more, but he was ready to begin his minor league journey.

“That was one thing Doug said, was the road you take to get there doesn’t matter,” Kendrick said. “It’s still going to be an opportunity, so I’m going to take it and make the most of it.”

With his contract signed shortly after the draft, Kendrick was officially a professional baseball player. He spent a few days in Vicksburg with his family, then headed west again to report to the Rangers’ Arizona League affiliate.

Clyde Kendrick, center, poses with his friends Marcus Williams, left and Jekori Reed in the dugout at Bazinsky Field. Kendrick, a former Vicksburg High star, was selected by the Texas Rangers in the 27th round of the Major League Baseball draft earlier this month.

The Arizona League season begins today. It’s one of the lowest levels of pro baseball. Its main purpose is to separate true prospects from also-rans, and challenge the mental toughness of players as well as their physical talent.

Kendrick said he’s well aware of the difficult road that lies ahead.

“It’s not going to be a piece of cake. It’s going to take grinding, staying humble, and keeping down the drama, and to strive to be the best I can be,” he said. “I want these guys to love me. That’s what I’m going to make them do, is make them love me. I’m going to strive for the best and show them I am who I am.”

Gomez, for one, had faith that his star player has all of the tools necessary to make the leap from late-round draft pick to major leaguer.

“Sometimes it’s a crapshoot. But in terms of skillset and ability, why not?” Gomez said. “There’s usually going to be a five-year limitation before a team decides whether you’ll make it or not. But he’s a guy who sees the urgency, and that it’s a job now. He’s going to go after it the same way as if he was starting any other career.”

When he was in high school, one of Kendrick’s summer travel teams played in a tournament at Rangers Ballpark in Arlington. Kendrick remembers it well.

“I made three diving catches in a row on that field,” he said with a grin.

With some hard work and perhaps a little luck, Kendrick might be finding himself trotting out of the bullpen and onto center stage at the pitcher’s mound in the near future. He admits he’s thought about it, and breaks out an even bigger grin when he describes it.

“That would just be the best feeling in the world, to know that I made it and made my dream come true, and put in the hard work to get there,” Kendrick said. “Nobody can stop me but me. To see myself coming out of the pen and 50,000 people looking at me … oh my. That’d be sweet.”