Church of the Holy Trinity to host program focused on ‘Reconciliation Windows’

Published 2:07 pm Friday, January 3, 2020

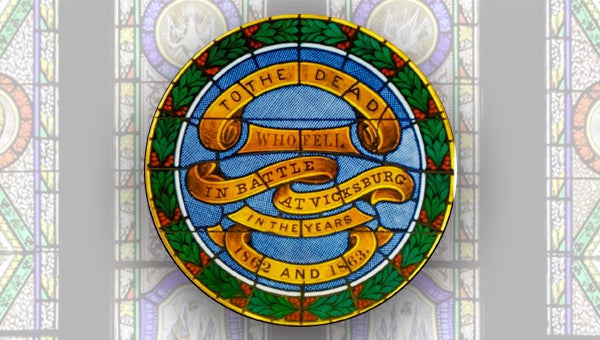

The 4-foot 8-inch circular window sitting above three stained glass windows in the nave of Church of the Holy Trinity carries a sobering, unifying legend: “To The Dead Who Fell In Battle At Vicksburg In The Years 1862 And 1863.”

“In terms of who is memorialized by the Reconciliation Memorial windows, the above dedication from the main window encompasses those killed in battle at Vicksburg, not at the numerous other places where combatants were killed in the whole of the Vicksburg Campaign,” church member Timothy Ables said.

“For the Union, that means a total of 974 dead,” he said, “208 killed at Chickasaw Bayou in December 1862, 672 in the May 18-22 1863 skirmishes at Vicksburg and assaults on the defensive lines, and 94 during the May 23-4 July 1863 siege operations.

“For the Confederacy, it means a total of 939 dead, 63 at Chickasaw Bayou, 1 on April 22, 1863, during the river batteries action, and 875 during May 18-4 July 1863 defensive and siege operations.”

Jan. 21, the members of Trinity Episcopal Church will hold a special program at 6 p.m. honoring what is known as the “Reconciliation Windows as part of their observance of the church’s yearlong 150th anniversary.

The windows were first stained glass windows installed in the church in 1880, 11 years after the church began, said the Rev. Andy Andrews, Church of the Holy Trinity’s rector.

The congregation, Andrews said, thought the words in that circular window “were a pretty strong sentiment, especially with Vicksburg being in the midst of reconstruction and feelings after the war were still very raw, and that act of reconciliation still has a message that can ring for us today.”

He said the Jan. 21 program will be an opportunity to tell the story of the windows.

Andrews said Jere Nash, a Democrat and political consultant, and Andy Taggart, a Republican, lawyer and Madison County supervisor, will tell stories of Mississippi politics “where people on different sides have joined together and put their differences aside to move forward together, and maybe inspire us in 2020 to have a better sense of how we can carry on a healthy conversation with others, especially politics.”

The men, he said, are friends and have written books on Mississippi politics.

The featured speaker for the program is Bishop Kee Sloan of Alabama, a Vicksburg native who grew up as a member of Holy Trinity.

Andrews said the program begins at 5:15 p.m. with “cornbread and soup,” and then the speakers at 6 p.m.

“Anybody and everybody to whom this sounds interesting is welcome to come.”

The Reconciliation Memorial windows were installed in January 1880, not long before the first worship service in the completed church on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1880.

The windows were the first of an eventual 32 memorial windows in the church, and they represent a very early gesture toward helping heal the sectional divide following the Civil War, though a gesture meaningful at the outset only to certain segments of the population, North and South.

The details of the left tall inner window in the Reconciliation Memorial show the flags, shield and discarded war instruments of the lost Confederacy, while the right inner window shows the flag, shield and war instruments of the restored United States.

Holy Trinity Church was founded in 1869 when 60 individuals, members of first Christ Episcopal Church, Vicksburg’s first Episcopal parish, gathered in the downtown office of a leading physician.

The group had worked for more than a year to start a new parish and received their bishop’s consent.

The Reconciliation Memorial windows were conceived in the early 1870s by the Rev. Dr. William W. Lord, Holy Trinity’s first rector. Dr. Lord first served at Vicksburg as rector of Christ Church from 1854 to 1863, and with his family lived through the terror and hardships of the 47-day siege that ended July 4, 1863.

He held daily services throughout, despite near-constant shelling that destroyed the rectory and heavily damaged the church. After the city was occupied, he and his family left for a section of the South not yet under Union attack or control.

He served hardship posts for the next two years as rector of Church of the Redeemer, Greensboro, Ga., and Christ Church, Winnsboro, S.C., his congregations being women, children, and the infirm.

At Winnsboro, his family again unhappily found themselves in the path of a Union army, and this time the church was burned.