Playmakers 2020: Months of work goes into the 40 seconds it takes to call a play

Published 3:00 pm Monday, August 31, 2020

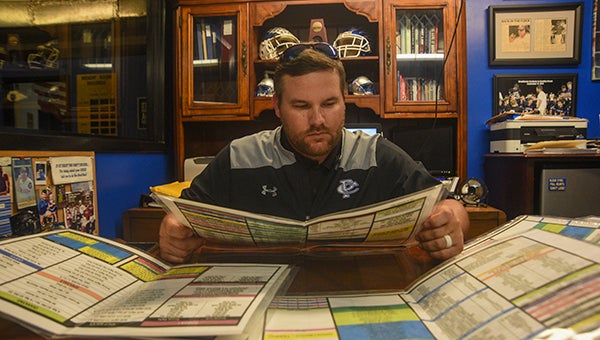

- Porter’s Chapel coach Blake Purvis looks over some of his old playcalling sheets. Calling a play during a game only takes a few seconds, but months of work go into getting it just right. (Courtland Wells/The Vicksburg Post)

The situation seems simple enough.

It’s second-and-2 from the 35-yard line, early in the second quarter. The next play will try to keep the chains moving, not win the game or even score a touchdown.

In a span of 40 seconds, however, a carefully orchestrated ballet is set in motion and executed. Players rush on and off the field. Decisions are made and communicated at warp speed from coaches to players, and then among teammates. The ball is snapped and a running back takes a handoff and gains three yards to get the first down. The game marches on and the play is quickly forgotten as the clock resets and the process repeats itself.

It’s a basic sequence that doesn’t appear, on the surface, to have taken a lot of thought or effort. In reality, it is a complex and intricate task. Designing a play, naming it, teaching it and calling it on Friday night is a process that can take months, if not years, to pull off.

“(Fans) have no idea” how much goes into it, Porter’s Chapel Academy coach Blake Purvis said with a chuckle. “The amount of time that goes into offensive and defensive schemes, and strategies and that stuff is more than just two hours at practice a day.”

DRAWING UP THE PLAYBOOK

Every play that gets called in a game started off as an idea — probably from someone besides the coach who calls it.

Warren County’s coaches admitted to finding inspiration from a variety of sources, from watching NFL or college games to things they’ve been taught throughout their careers. They, like the rest of their colleagues around the state, are not shy about stealing a good idea.

“I’ve got a whiteboard in my office at my house that has football plays drawn on it,” Purvis said. “When I’m sitting at home paying bills something comes into my mind. Once I start drawing on that, whatever I’m doing stops for 30 or 45 minutes. Watching football games just on TV, old games and stuff like that, you pick up on things.”

The next step is the hard part — figuring out how to adapt a play to fit their own systems, personnel and terminology.

Every play has a name, a word salad of numbers, directions and insider terms that resemble a foreign language to the untrained ear. In reality, each part of the play’s name has a simple meaning. One word will detail the way the linemen are supposed to block. Another tells the running back which side of the line he’s supposed to run toward. Numbers tell the receivers which route they should run.

Each word is carefully chosen to be short and unique. Two similar-sounding words in different plays might be misheard in a loud environment. Keeping terms short and unique helps avoid confusion, and is easier to teach and communicate.

“It sounds crazy, but calling a play is like walking into McDonald’s,” Vicksburg head coach Todd McDaniel said. “You don’t walk in and say, ‘Give me a Quarter Pounder, and I want a fry and a Coke.’ No. You just say, ‘I want a No. 1.’ That’s all it is. No. 1, this is what it is. But it takes repetition for them to understand, ‘I just want a No. 1.’”

In keeping with that theme, McDaniel added, players sometimes take it a step further by creating their own shorthand. A specific play that the Gators use several times per game might get its own nickname instead of the formal one from the playbook.

“Over time, the kids will break it down themselves. The kids might break it down to ‘F5! F5! F5!’ Everybody knows what it is and I don’t have to say all of that stuff. Over the course of time, it’ll break it down to one word,” McDaniel said.

Creating standard terminology also allows coaches to create and adjust plays on the fly. By tweaking the order of the words in the call, they can flip the formation, put a player in motion, or change the direction of the play. That gives the appearance of a different play, even though it’s one they might run a lot.

“The scheme, the play call itself, is going to take care of all of your linemen. They’re going to learn a scheme by one or two words — iso, power, counter — and all five of them know what to do,” Purvis said. “Our receiver routes are mostly numbers. That tells all four receivers what to do because they’ve learned it as a concept. And then we have a motion word for right and left. Once they learn what right and left motion is, I can call any play, in any formation, with any motion, and the play call tells them the rest of what to do.”

PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT

The best play in the world is worthless if players don’t know how to execute it. The process of turning the diagrams in the playbook to success on the field starts in the offseason.

“I started that in March,” McDaniel said with a laugh.

Beginning with spring practice, time spent in front of a whiteboard is as important as time spent on the field. Spring and summer is when players learn the playbook, from the terminology to their individual assignments. They also take it from the classroom to the field by learning where to stand between plays and how to decipher signals from the sideline.

Warren Central head coach Josh Morgan often gesticulates wildly as he calls the team’s defensive plays. With so many moving parts, he said teaching terminology and signals during the offseason is critical to success in the fall.

“The earlier you can start that process, the better it’s going to be for you as a coach,” Morgan said. “The earlier you can get them familiar with it, it just broadens the whole spectrum of what you can install in terms of your terminology.”

Teams have three methods of calling a play. Coaches will either tell it to a player, who takes it to the huddle; call out a code word that leads to a call on a printed wristband; or through a series of intricate hand signals. All three are used in the course of the game, depending on the situation.

“Defensively, we make all of our kids learn our signals,” McDaniel said. “Offensively, we use wristbands, we use signals, or we’ll huddle and use words. I prefer the huddle. I’m a huddle guy. I’m not a fast guy.”

Individual plays are also practiced, of course — over and over again, with different variations and wrinkles, until each one is burned into the brains of players and coaches alike. No play works 100 percent of the time, but the goal of the offseason is to drill players on the ones that will be used most and create a reflex action.

“We get our basic offense and just rep it and rep it and rep it. If it’s not muscle memory then they’re going to get pressure, they’re going to hear people in the stands and all that,” St. Aloysius offensive coordinator Kacy Presley said. “Hopefully you’ll prepare enough plays that are base plays, and then you can adjust them so as the defense changes you can adapt with them.”

THE GAME PLAN

Most high school coaches have between 120 and 150 plays in their offensive playbook. Not all of them are suitable to use against a given opponent, so one of the first jobs each week is to figure out how many and which ones they’ll need.

The cuts are made based on a number of factors, from what has been working for their team to what looks like it’ll work against the next opponent. In crafting a game plan during meetings on Saturday and Sunday, coaching staffs will pick 75 or 80 plays for potential use.

“I look for certain things I’ve seen on film — down and distance, their tendencies. I like to believe that if you put yourself on film you’ve put your mind on film, and if you put your mind on film then I’ve got you. I’m going to find things you like to do and don’t like to do, and then transfer that information to my kids,” McDaniel said.

After picking the plays, coaches organize them into categories based on when they’re likely to be used. Certain passing plays, for example, might be under a heading for a third-and-8 situation. A read option play would be listed under second-and-4.

Once the plays are categorized, they are color-coded and put onto laminated cards for easy reference.

WHAT’S THE PLAY?

After months of practice and days of game planning, it’s finally time to call a play on Friday night. The play clock resets to 40 seconds as soon as the ball is set down from the previous play, and a blizzard of activity is set into motion.

In the first five seconds of those 40, coaches in the booth and on the field communicate with each other to assess the situation — down, distance, time and score. The next few seconds are spent checking the play sheet and finding the right one to call. Purvis said he and most coaches try to think at least one step ahead, although it doesn’t always go according to plan.

“I’m planning to do this, then hit them with this and then with this. Obviously, what happens on one play can change what you want to call next,” Purvis said. “When I call one play, I have a good idea what I want to come behind it with. Maybe 50 percent of the time do I come behind it with what I wanted to.”

By the time the play clock hits 30 seconds, substitutions are being made and the call is signaled in. That’s where the offseason work of learning where to stand on the sideline comes into play. First- and second-stringers are taught to follow coaches and always be ready.

“They’re right with me, and hopefully we’ve repped it enough so that however we signal the play in we’re going to give it to him or signal it in on the wristband,” Presley said. “The linemen will be with the O-line coach and he’ll keep an eye on them and sub them in. The skill guys are going to be with me. Then maybe you’ll have another coach that works with the younger guys and he’ll keep them close by so they can pay attention and learn for when their number’s called. Everything is a habit.”

As the play is signaled in, teammates start communicating it to each other. That can be especially important on defense, where it might be difficult for a player on the opposite side of the field to see or hear a coach’s signal.

Again, Morgan said, training, practice, teamwork and personal responsibility are vital in those 10-15 seconds. It’s as important for them to make sure their teammates have the right call as it is for the coaches to make the right selection and signal it in correctly.

“A lot of times players will handle that. They’ll get the call if they missed it,” Morgan said. “A lot of times us as coaches will resend it as much as we can. What we don’t want is their eyes on us when the ball is snapped, so we’ll resend it until we get in that danger zone of them hiking the football. But a lot of that is verbiage and leadership on the football field. Our leaders usually handle that.”

Between 25 and 10 seconds on the play clock, depending upon whether a team huddles or not, adjustments are made based on the formation or audibles. Some offenses signal in a different play once at the line, and both the offense and defense adjust to it. In no-huddle situations, the entire process might take less than 20 seconds.

“It’s a lot that happens in 30 seconds,” Purvis said with a laugh.

At some point after that, the ball is snapped and the play is run. Months of preparation come to a head. One team is successful and the other is not. Either way, there’s no time to dwell on it. The train of organized chaos needs to run on schedule, 40 seconds at a time, all night long.

“It’s 40 seconds from the spot of the ball to a play. I know that sounds like a lot, but it is not a lot. A lot goes into it, as far as preparation,” Morgan said. “It’s really a beautiful thing. It’s a pretty smooth thing to watch.”