Mississippi corrections commissioner discusses seminary plan with Vicksburg Rotarians

Published 11:10 am Tuesday, August 10, 2021

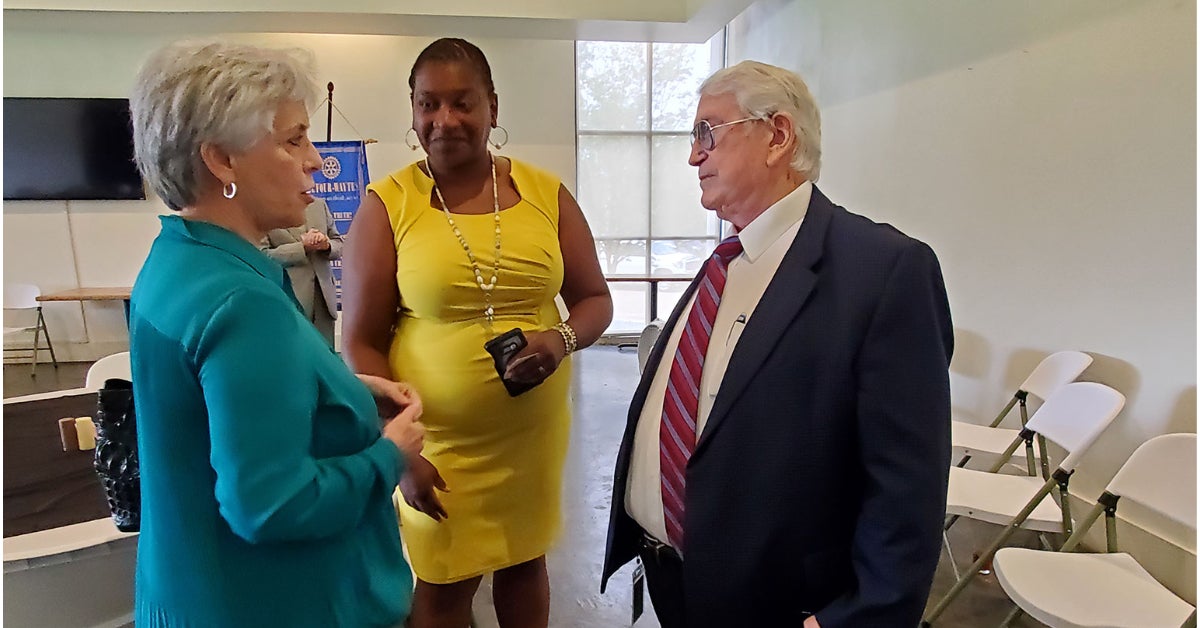

- Warren County Judge Marcie Southerland, left, and Circuit Judge Toni Terrett, center, talk with Mississippi Commissioner Burl Cain after Cain's address to the Vicksburg Rotary Club Thursday. (Photo by John Surratt)

Mississippi’s commissioner of corrections is taking a new approach to reducing violence and gang activities in the state’s prisons by using a formidable ally — God.

“If you’re going to make prisons work, you want morality, first and foremost,” state Commissioner of Corrections Burl Cain told Vicksburg Rotarians Thursday. Cain, who was warden of the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, La., for 21 years, was appointed Mississippi’s commissioner of corrections in May.

His plan to reform the prison system employs a successful program he instituted at Angola with the help of the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. The program, Cain said, has already produced some results, pointing out that violence at the State Penitentiary at Parchman dropped 52 percent in one year.

“That’s a big deal. Here’s how we did it: The inmates were busy in a seminary we started,” he said. “We had a seminary in Louisiana and when we did, the violence went away. We just let the inmates be the agents of change.”

Cain said he began the seminary program at Angola in 2004. Under the program, inmates who qualify can earn a degree in theology. The graduates then establish churches in the prison to bring other inmates together for services and religious education.

He said the program is paid for through private funds.

“You have to have a high school diploma and you have to qualify for seminary — meet the academic standards of the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary,” Cain said. “If you qualify for the academic standards then you can go to the seminary. We don’t choose religions; we let you qualify. If you qualify, you can go.”

The only provision, he said, is the inmate must sign a contract that they won’t question the theology or the curriculum and will accept the curriculum for the next four years without debate.

“What they’re (the seminary staff) doing is teaching theology, because morality comes quicker in religion than anywhere else in a prison environment,” Cain said. “We’re looking for morality to have more rehabilitation. So they train these guys for four years, just like the (regular) seminarians. It’s the same curriculum they have in New Orleans, same qualifications accredited by the SACS (Southern Association of Colleges and Schools), and at the end of four years you’re a theologian.”

The goal, Cain said, is for inmates to graduate from the seminary and then plant a church inside the prison.

He said plans call for churches at each facility in the state — two at Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl; two at Parchman; one at South Mississippi Correctional Facility in Leakesville; and one at Marshall County Correctional Facility, a private prison in Holly Springs which the state will take over in the fall.

A church is also planned for a proposed rehabilitation facility at Walnut Grove.

“We have to have one everywhere,” Cain said.

The seminary graduates, he said, are trained to establish their church “just like a preacher being a missionary in a foreign country.”

“When they plant their church, what they’re doing is planting a gang,” Cain said. “But it’s a positive gang that we all can live with and prosper and do well because they’re going to be the preacher and they’re going to get them a group and they’re going to teach them the principles but also teach them morality, the golden rule and the 10 Commandments.

“That brings about a culture of change to the prison when you have enough of those guys teaching a number of inmates then you replace the gangs with gangs for God.”

That’s what happened at Angola, Cain said, adding a five-year, $1.3 million study of the program at Angola by Baylor University proves that it works. Money for the study, he said, was raised through private contributions.

One part of the program, Cain said, is that it takes about 10 years to become an institution in the prison, “Because we want you to get the degree and that takes four years, and then we want you to be able to stay with us long enough to plant some churches and do some good to change the culture of the prison.”

What happens with the program, he said, is the inmates who complete the program are well-behaved “and they’re the cream of the crop. So when you have (early release) laws passed like we just had in Mississippi, some of those guys are going to be eligible for parole. These guys become the model prisoners,” he said.

“Those are the kind that’ll go to the parole board and parole out and let them go, which is real good because they’ll go back to the urban areas where they came from and they’ll have the moral background for them to be able to change the culture in the urban area. They get paroled, they’re free people; freemen.”

What Cain did to help the seminary program, was bring several paroled former inmates from Angola to be chaplains.

“We didn’t have a lot of time. Being a four-year appointment, I had to speed up the system as fast as I could, so I got some (parolees) already trained, who already knew what to do and were already field ministers to come to teach the ones in Mississippi we had already graduated but didn’t know how to do it.

“They’re chaplains; they have free rein to go all over the prison and mingle like a chaplain should,” Cain said.

He said a “free world” chaplain “would not feel comfortable going down into the bowels of the prison unescorted by themselves day or night and deliver things like death messages, where these guys (the paroled chaplains) are uninhibited; they’ve been there and done that and they have status with other prisoners because most of them were lifers.

“They’re more effective than a free world chaplain that has never been in a prison before,” Cain said.

Besides the seminary program, Cain said he is working on a program to prepare inmates to re-enter society by teaching them a trade and skills.

“This is not sweeping a floor with a broom,” he said, adding the inmates will learn skills like welding and other trades to be job-ready when they are released.

The legislation has not been prepared for the program, he said.